LIDA* rose the insulin requirement

By Warren R. Heymann, MD

April 14, 2021

Vol. 3, No. 15

Amyloidosis, I thought I knew ye. But alas, you fooled me again.

Amyloid is an insoluble protein folded in β-pleated sheets that is deposited extracellularly. Amyloid can accumulate in one or many organs, thereby causing dysfunction. There is an increasing number of proteins identified to be amyloidogenic. The common amyloid entities are AL (amyloid light chain), AA (amyloid associate), ATTR (transthyretin), and β2-microglobulin. Systemic amyloidosis consists of primary systemic amyloidosis (AL amyloidosis), secondary systemic amyloidosis (AA amyloidosis), and dialysis-associated amyloidosis (β2-microglobulin). Skin changes such as petechiae, ecchymoses, waxy papules and plaques, nail dystrophy, and, rarely, blisters may occur.

Cutaneous amyloidosis may be primary or secondary. The latter refers to deposition of amyloid within skin tumors, such as seborrheic keratosis and basal cell carcinoma, and is detectable histologically. Primary localized cutaneous amyloidosis (PLCA) is characterized by the deposition of amyloid in the skin without involving any internal organ, including lichen amyloidosis, macular amyloidosis (keratinic amyloid in both types, derived from degenerated keratinocytes), and nodular amyloidosis (AL amyloid, derived from immunoglobulin light chains). (1)

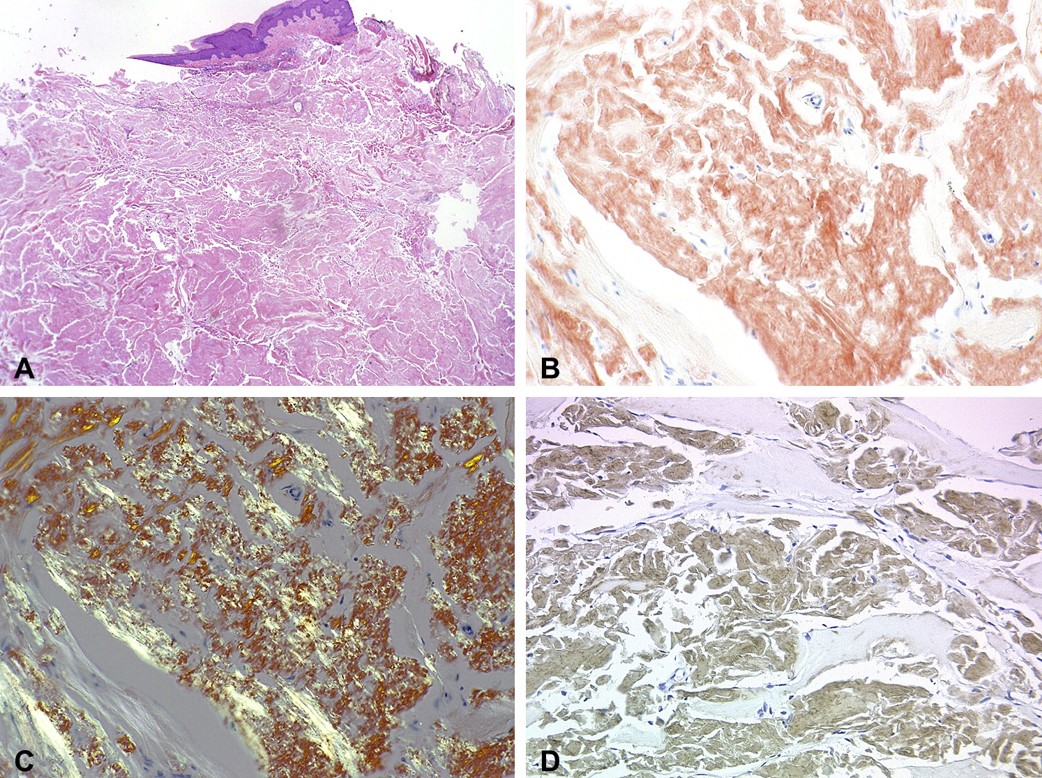

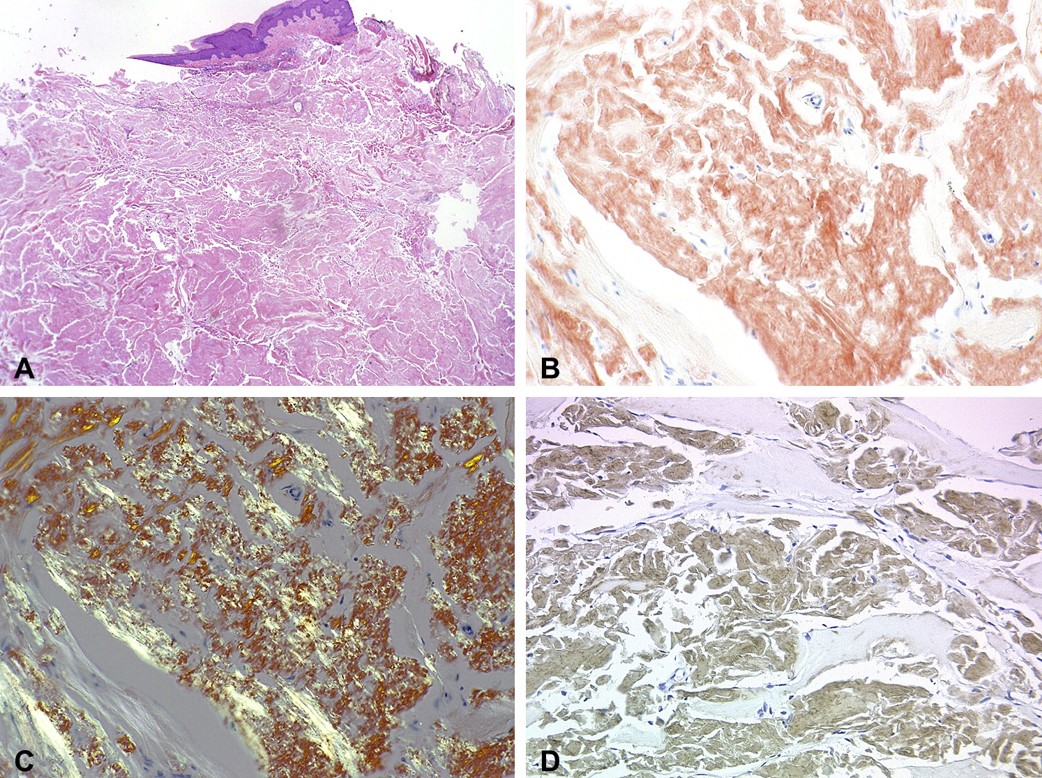

Recently there has been a flurry of articles describing localized insulin-derived amyloidosis (LIDA). Recognizing LIDA is crucial, because it has an important effect on glycemic control. In 1983, Störkel et al observed that subcutaneous tissue from one diabetic patient and six Wistar rats, having received a continuous local infusion of insulin daily for 6 weeks, demonstrated granulation tissue and extracellular deposits showing green birefringence under polarized light when stained Congo red.

Immunohistologically, they displayed binding of anti-insulin antibody. Electron microscopy demonstrated a typical fibrillar structure with a fibril diameter of 60 to 80 A. These findings confirmed that the deposited substance was insulin-derived amyloid. (2)

According to Chen and Lee, LIDA is a rare subcutaneous adverse effect of insulin injection, most commonly presenting as a firm, painless, subcutaneous nodule of about 20–50 mm (extreme range 10–120 mm) at the injection site. LIDA is usually noted on the abdomen but also frequently noted on the arms or thighs. There is an equal distribution of Type 1 and Type 2 diabetes. LIDA predominantly affects male patients, with a sex ratio of about 2:1, with a similar average age of male and female patients in the late 50’s. (3) Occasionally, overlying changes of acanthosis nigricans may be observed (4). Lesions may exist without a palpable mass (5) or may present as exophytic brownish nodules. (3) Necrotic tissue has been reported around amyloid deposition. (6)

As detailed in a case by Nagase et al, MRI of the insulin injection sites may demonstrate heterogeneous hypointense streaks in the subcutaneous fat tissue, while ultrasonography may reveal hyperechoic streaks with loss of the normal layer structure of the subcutaneous fat tissue. Histological examination after fine‐needle aspiration biopsies showed insulin‐derived amyloidosis. (5) Such imaging techniques may obviate the need for more invasive skin biopsies in selected patients.

Aside from the classical histological features of amyloidosis, some cases may demonstrate calcification or spherical bodies (so-called insulin amyloid bodies). While Congo red staining demonstrates amyloidosis, LIDA can only be confirmed by immunohistochemistry or mass spectrometry demonstrating insulin derivation of the amyloid deposits. (4).

Aside from the rare LIDA, subcutaneous insulin injection may cause other site-related lesions, such as lipoatrophy, insulin-induced cutaneous lipohypertrophy (IICL), and allergic reactions. It is essential to differentiate IICL from LIDA. IICL is caused by the lipogenic and anabolic properties of insulin. It may affect half of all diabetic patients utilizing insulin. Clinically, the lesions are softer, and will abate with cessation of insulin injection at that site. Interestingly, IICL and LIDA may coexist in the same lesion.

Most importantly, LIDA causes an impairment of the insulin absorption at the injection site resulting in an unpredictable release of insulin from the nodules, leading to poor glycemic control. Patients favor injecting insulin in these lesions because they are painless. Endo et al reported a case a 70-year-old diabetic woman with LIDA presenting with hypoglycemia. (7) Optimal treatment of LIDA requires surgical excision of the lesion — this will result in a dramatic decrease in the patient’s insulin requirement and an improvement of glycemic control. (8)

LIDA is likely an underrecognized disorder, possibly due to unfamiliarity with the entity (I am guilty as charged!) or because such lesions are subclinical (those presenting without masses), or mistakenly diagnosed as IICL. The importance of differentiating IICL from LIDA cannot be overemphasized. What remains an enigma is how and why amyloid is derived from insulin — unlocking that mystery could prevent the appearance of LIDA and its attendant mischief in glycemic control.

(Ever since seeing The Music Man as a 7-year-old boy, I have been smitten by Meredith Wilson’s brilliant score — throughout writing this commentary, I could not stop singing the beautiful barber shop rendition of Lida Rose — enjoy!)

Point to Remember: Recognizing localized insulin-derived amyloidosis (LIDA), a rare complication of insulin, is essential because of its potential havoc on glycemic control. Surgical excision of LIDA offers optimal management.

Our expert’s viewpoint

Justin Endo, MD, MHPE

Associate Professor, University of Wisconsin Dermatology

I am honored Dr. Heymann read my case report that I wrote as a resident. Perhaps he has given me too much credit, because my name (Endo) implies I am a dermato-endocrinologist!

The pathophysiology of LIDA is presumed to be from repeated injections without site-rotation, which leads to inflammation, amyloid accumulation, and impaired insulin absorption. My patient declined surgery, but a diabetic educator helped my patient improve glycemic control by rotating injection sites and counting carbohydrates.

There does not appear to be a convincing association between LIDA and the type of insulin formulation. Localized cutaneous amyloidosis has also been rarely reported with enfuvirtide. I wonder if other injected peptides have the potential to do so but are waiting to be discovered — perhaps by a resident looking for a case report like me years ago!

As Dr. Heymann pointed out, amyloidosis encompasses heterogenous conditions. To avoid unnecessary angst and invasive testing, it is important to clearly articulate to our patients and non-dermatology colleagues about the difference between (non-AL) primary localized cutaneous amyloidosis and systemic amyloidosis. Having trained as an internist in a past life, the usual connotation of “amyloid” is the systemic type.

William YM, Chan LY. Amyloidosis. In Lebwohl MG, Heymann WR, Berth-Jones J, Coulson I (eds). Treatment of Skin Disease, Fifth edition. Elsevier, 2018, London, pp 34-36.

Störkel S, Schneider HM, Müntefering H, Kashiwagi S. Iatrogenic, insulin-dependent, local amyloidosis. Lab Invest 1983; 48: 108-111.

Chen MC, Lee DD. Atypical presentation of localized insulin-derived amyloidosis as protruding brownish tumors. Clin Exp Dermatol 2020; 45: 353-355.

Carll T, Antic T. An abdominal wall mass of exogenous insulin amyloidosis in setting of metastatic sarcoma. J Cutan Pathol 2020; 47: 406-408.

Nagase T. Iwaya K, Kogure K, Zako T, et al. Insulin-derived amyloidosis without a palpable mass at insulin injection site: A report of two cases. J Diabetes Investig 2019 Dec 22. doi: 10.1111/jdi.13199. [Epub ahead of print].

Iwaya K, Zako T. Fukunaga J, Sörgjerd KM, et al. Toxicity of insulin-derived amyloidosis: A case report. BMC Endocr Disord 2019; 13;19:61.

Endo JO, Röcken C, Lamb S, Harris RM, et al. Nodular amyloidosis in a diabetic patient with frequent hypoglycemia: Sequelae of repeatedly injecting insulin without site rotation. J Am Acad Dermatol 2010; 63: e113-e114.

Ansari AM, Osmani L, Matsangos AE, Li QK. Current insight in the localized insulin-derived amyloidosis (LIDA): Clinicopathological characteristics and differential diagnosis. Pathol Res Pract 2017; 213: 1237-1241.

All content found on Dermatology World Insights and Inquiries, including: text, images, video, audio, or other formats, were created for informational purposes only. The content represents the opinions of the authors and should not be interpreted as the official AAD position on any topic addressed. It is not intended to be a substitute for professional medical advice, diagnosis, or treatment.

DW Insights and Inquiries archive

Explore hundreds of Dermatology World Insights and Inquiries articles by clinical area, specific condition, or medical journal source.

All content solely developed by the American Academy of Dermatology

The American Academy of Dermatology gratefully acknowledges the support from Incyte Dermatology.

Make it easy for patients to find you.

Make it easy for patients to find you.

Meet the new AAD

Meet the new AAD

2022 AAD VMX

2022 AAD VMX

AAD Learning Center

AAD Learning Center

Need coding help?

Need coding help?

Reduce burdens

Reduce burdens

Clinical guidelines

Clinical guidelines

Why use AAD measures?

Why use AAD measures?

Latest news

Latest news

New insights

New insights

Combat burnout

Combat burnout

Joining or selling a practice?

Joining or selling a practice?

Advocacy priorities

Advocacy priorities

Promote the specialty

Promote the specialty