Men in the Twilight Zoon

By Warren R. Heymann, MD

February 19, 2020

Vol. 2, No. 7

It is a dimension as vast as space and as timeless as infinity. It is the middle ground between light and shadow, between science and superstition, and it lies between the pit of man's fears and the summit of his knowledge. This is the dimension of imagination. It is an area which we call the Twilight Zone – Rod Serling

It is not difficult to tell when men are anxious about genital lesions. Coming into the examination room, they may be fidgeting with evident forehead hyperhidrosis, as they politely request that my medical assistant leave the room so we can have a private conversation. Perhaps I am generalizing, but men with penile lesions have three questions (priority depending on their sexual history): 1) is it venereal? 2) Can I spread it? 3) Is it cancer? Giving the diagnosis of Zoon balanitis (ZB) offers patients a sense of relief because the answer to these questions is virtually always no. While it may be satisfying to afford patients a diagnosis, when it comes to understanding ZB, we are still in the twilight zone.

ZB usually affects middle-aged to older men who are uncircumcised; it is an idiopathic, chronic, benign inflammatory mucositis. ZB is also known as balanitis circumscripta plasmacellularis or plasma cell balanitis of Zoon. Although described as rare in the literature, ZB is probably underdiagnosed. Analogous lesions have been described in females with similar clinical and histological features of ZB and termed as Zoon vulvitis, plasma cell vulvitis, or vulvitis circumscripta plasmacellularis. (1) “Zoon-like” lesions have also been described on the oral mucosa and conjunctiva, where the term “idiopathic lymphoplasmacellular mucositis-dermatitis” has been proposed. (2)

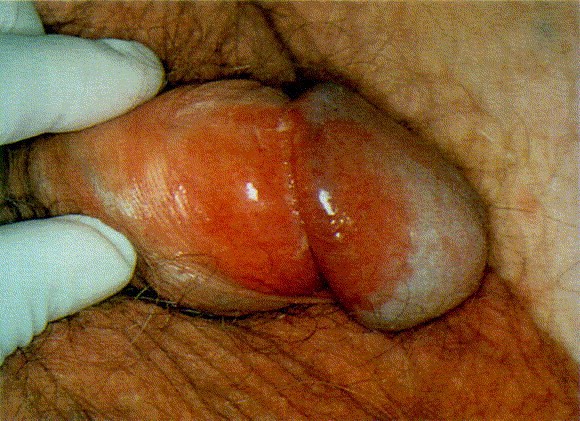

Classically, ZB presents as symmetrical, well-marginated, erythematous, shiny plaques with multiple pinpoint redder spots (“cayenne pepper spots”) involving the glans, prepuce, or both. Vegetative, erosive, and multiple lesion variants have also been described. Usually, ZB is asymptomatic, although pruritus may be present. The course tends to be chronic and may persist for months to years. Also, ZB may be poorly responsive to topical treatment. (3)

Before arriving at a diagnosis of ZB, other entities in the broad differential diagnosis need to be ruled out by biopsy, culture, KOH examination, or patch testing. In alphabetical order these include: candidiasis, contact dermatitis (irritant or allergic), fixed drug eruption, herpes simplex virus, lichen planus, lichen sclerosis, pemphigus vulgaris, penile intraepithelial neoplasia (erythroplasia of Queyrat), psoriasis, reactive arthritis, squamous cell carcinoma, and syphilis. (4)

Histopathologically, epidermal atrophy, lozenge-shaped keratinocytes, spongiosis, and a dense lichenoid infiltrate composed largely (> 50%) of plasma cells are observed. Erythrocyte extravasation and hemosiderin deposition are often appreciated, corresponding to the cayenne spots observed clinically. (3)

Advances in differentiating ZB from other entities include reflectance confocal microscopy (RCM) and dermoscopy. Arzberger et al, utilizing RCM, demonstrated a nucleated honeycomb pattern and vermicular vessels in patients with balanitis. (This was demonstrated beautifully on an accompanying video — definitely worth a look!) Scattered small bright cells and round vessels were present in all lesions. The adjacent normal skin showed a typical honeycomb pattern and round papillary vessels. The most relevant RCM criteria for carcinoma in situ (CIS) were atypical honeycomb pattern, disarranged epidermal pattern, and round nucleated cells. The authors concluded that they were able to differentiate balanitis from CIS, suggesting that RCM may be helpful in avoiding biopsies at this sensitive site. (5) Errichetti et al demonstrated that dermoscopy of ZB was characterized by orange structureless areas (focal or diffuse) and vessels (linear to curved). (6)

Therapeutically, first-line therapy continues to be circumcision — the only treatment providing a long-term, complete remission. For those patients who decline surgery, other options include topical steroids, calcineurin inhibitors, mupirocin, photodynamic and laser therapy, although the disease tends to relapse with the use of any of these modalities. (3,7)

ZB is in the twilight zone because the pathogenesis of the disorder is an enigma. Improvement following circumcision suggests that poor genital hygiene, chronic irritation, or chronic infection (with Mycobacterium smegmatis) may be at play. (3) Some authors have speculated that irritation by urine in the context of a “dysfunctional prepuce” (whatever that means) may be the etiology. In a case-control study of 30 patients with ZB compared to 54 control patients with other dermatologic disorders, the only statistically significant factors associated with ZB were smoking and poor genital hygiene (based on the number of weekly foreskin retractions). (2)

So many questions remain — is ZB the same disease as Zoon vulvitis or the Zoon-like disorder of other mucous membranes? Is ZB a disease sui generis or just a reaction pattern? (I favor the latter hypothesis.) Until such questions are addressed, we will remain in the Twilight Zoon.

Point to Remember: Zoon balanitis is a diagnosis of exclusion. Although prevalent in uncircumcised men, other factors must be at play for Zoon vulvitis or Zoon-like disorders of other mucous membranes.

Our Expert’s Viewpoint

Philip R. Cohen, MD

Dermatologist

San Diego Family Dermatology, National City, California

Adjunct Professor of Dermatology

Touro University California College of Osteopathic Medicine, Vallejo, California

I coauthored a paper on Zoon balanitis (ZB) 25 years ago (Davis DA, Cohen PR. Balanitis circumscripta plasmacellularis. J Urol 1995; 153: 424-426). At that time, a skin biopsy was the standard in establishing the diagnosis and circumcision was the first-line therapy. Two decades later, I diagnosed a man with ZB and decided to topically use mupirocin 2% ointment on the biopsy site and the entire affected area of his glans penis and foreskin; there was partial clearing of the condition after 3 weeks and complete resolution after 3 months. (7) I was subsequently able to confirm this therapeutic observation of rapid improvement of ZB after treatment with mupirocin 2% ointment. (4) Therefore, when the diagnosis of ZB is a clinical consideration, a trial of topical mupirocin 2% ointment prior to biopsy could be initiated; in addition to successful resolution of the dermatosis, clearance of the lesion would also presumably establish the diagnosis of ZB since all of the other morphologically similar skin conditions of the penis and prepuce would not resolve using topical mupirocin 2% ointment as monotherapy. (Cohen PR. Topical mupirocin 2% ointment for diagnosis of Zoon’s balanitis and monotherapy of balanitis circumscripta plasmacellularis. Int J Dermatol 2019; 58: e114-115).

Dayal S, Sahu P. Zoon balanitis: A comprehensive review. Indian J Sex Transm Dis AIDS 2016; 37: 129-138.

Piaserico S, Orlando G, Kinder MD, Cappozzo P, et al. A case-control study of risk factors associated with Zoon balanitis in men. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol 2019; 1591-1594.

Lepe K, Salazar FJ. Balanitis circumscripta plasmacellularis (plasma cell balanitis, Zoon balanitis). StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing Jan 2019.

Bari O, Cohen PR. Successful management of Zoon’s balanitis with topical mupirocin ointment: A case report and literature review of mupirocin-responsive balanitis circumscripta plasmacellularis. Dermatol Ther (Heidelb) 2017; 7: 203-210.

Arzberger E, Komericki P, Ahlgrimm V, Massone C, et al. Differentiation between balanitis and carcinoma in situ using reflectance confocal microscopy. JAMA Dermatol 2013; 149: 149: 440-445.

Errichetti E, Lailas A, DiStefani A, Apalla Z, et al. Accuracy of dermoscopy in distinguishing erythroplasia of Queyrat from common forms of chronic balanitis: Results from a multicentric observational study. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol 2019; 33: 966-972.

Lee MA, Cohen PR. Zoon balanitis revisited: Report of balanitis circumscripta plasmacellularis resolving with topical mupirocin ointment. J Drugs Dermatol 2017; 16: 285-287.

All content found on Dermatology World Insights and Inquiries, including: text, images, video, audio, or other formats, were created for informational purposes only. The content represents the opinions of the authors and should not be interpreted as the official AAD position on any topic addressed. It is not intended to be a substitute for professional medical advice, diagnosis, or treatment.

DW Insights and Inquiries archive

Explore hundreds of Dermatology World Insights and Inquiries articles by clinical area, specific condition, or medical journal source.

All content solely developed by the American Academy of Dermatology

The American Academy of Dermatology gratefully acknowledges the support from Incyte Dermatology.

Make it easy for patients to find you.

Make it easy for patients to find you.

Meet the new AAD

Meet the new AAD

2022 AAD VMX

2022 AAD VMX

AAD Learning Center

AAD Learning Center

Need coding help?

Need coding help?

Reduce burdens

Reduce burdens

Clinical guidelines

Clinical guidelines

Why use AAD measures?

Why use AAD measures?

Latest news

Latest news

New insights

New insights

Combat burnout

Combat burnout

Joining or selling a practice?

Joining or selling a practice?

Advocacy priorities

Advocacy priorities

Promote the specialty

Promote the specialty