Propranolol and neutrophilic dermatoses: Can beta-blockade be better blockade?

By Warren R. Heymann, MD, FAAD

December 8, 2021

Vol. 3, No. 48

Once this seminal observation was established, it was only natural that the nonselective β-blocker propranolol (and topical timolol in some cases) be utilized, somewhat successfully, for a host of vascular disorders including pyogenic granuloma, Kaposiform hemangioendothelioma, tufted hemangioma, Kasabach-Merritt syndrome, angiolymphoid hyperplasia with eosinophilia, Kaposi sarcoma, angiosarcoma, flushing, rosacea erythema, and adrenergic urticaria. (1,2,3,4)

As Oberlin eloquently states: “Propranolol is a nonselective beta-blocker with a structure similar to catecholamines and thus competes for β-adrenergic receptors. Blocking β1-receptors is cardioselective, leading to decreased heart rate and myocardial contractility, while blocking β2-receptors leads to inhibition of smooth muscle relaxation and decreased glycogenolysis. The endothelial cells of IH express β2-adrenergic receptors; the mechanistic role of propranolol in these lesions is surmised to be due to vasoconstriction, decreased angiogenesis through inhibition of vascular endothelial growth factor, and subsequent endothelial cell apoptosis.” (1)

Propranolol continues to surprise.

Neutrophils have multiple functions in health and disease. They are short-lived cells, circulating for 10 hours. After apoptosis, these cells are phagocytized by monocytes or migrate into tissues. Cell death occurs after 4-5 days. Specific cell receptors are involved in the regulation of neutrophil function. These receptors affect adhesion, apoptosis, generation of reactive oxygen species (ROS), and activation of neutrophils under the influence of lipopolysaccharide (LPS). Neutrophils express membrane β-adrenoceptors, which contributes to regulation of neutrophil function by the neuroendocrine system and immune system. Much remains to be learned about the role of β-adrenoceptors in activation of innate immunity and regulation of apoptosis in human neutrophils. Frolov et al have demonstrated that propranolol increases that rate of spontaneous apoptosis of neutrophils and suppresses the production of reactive oxygen species (ROS). (5)

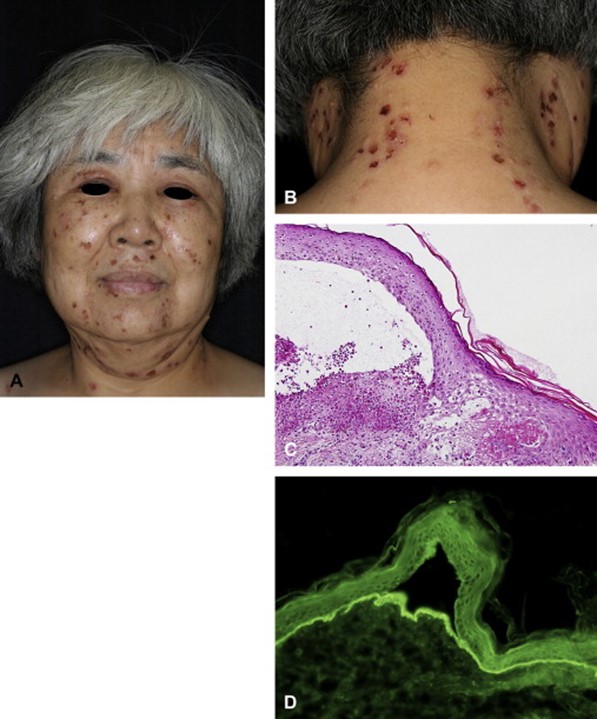

Neutrophil-mediated skin diseases, also known as the neutrophilic dermatoses (NDs), are due to altered neutrophil recruitment and activation, characterized by polymorphic cutaneous manifestations with possible internal organ involvement. Classical NDs include pyoderma gangrenosum, Sweet’s syndrome, subcorneal pustular dermatosis [Sneddon-Wilkinson disease], neutrophilic eccrine hidradenitis, bowel-associated dermatosis-arthritis syndrome, rheumatoid neutrophilic dermatitis, Behçet’s disease, amicrobial pustulosis of the folds (APF) and generalized pustular psoriasis. Neutrophils are also crucial in the pathogenesis of monogenic autoinflammatory syndromes such as cryopyrin-associated periodic syndromes, (6) immune complex-mediated diseases including leukocytoclastic vasculitis, and autoimmune bullous disorders such as bullous pemphigoid, epidermolysis bullosa acquisita, and dermatitis herpetiformis. In bullous disorders, ROS in concert with other neutrophil-derived proteases contribute to bulla formation.

In a fascinating study, Stüssel et al demonstrated that propranolol enhanced IL-8-induced neutrophil chemotaxis while reducing the release of ROS after immune complex stimulation. The authors performed RNA sequencing of immune complex-stimulated neutrophils in the absence and presence of the drug. They evaluated the impact of propranolol (topical and systemic) in a prototypical neutrophil-dependent skin disease, specifically, antibody transfer-induced epidermolysis bullosa acquisita (EBA) in mice, finding that the disorder improved by inhibiting neutrophilic activation while (paradoxically) enhancing chemotaxis. To validate the identified propranolol gene signature obtained in human neutrophils, they analyzed a selection of genes by RT-PCR in mouse epidermolysis bullosa acquisita skin and confirmed TNF, among others, to be differentially downregulated by propranolol treatment. Our data clearly indicate that, based on its molecular impact on immune complex-activated neutrophils, propranolol is a potential treatment option for neutrophil-mediated inflammatory skin diseases. (7)

In their commentary on Stüssel et al, Maglie et al conclude that “before designing clinical trials in humans, the anti-inflammatory mode of action of propranolol should be further dissected and related to other anti-inflammatory drugs, which have already proven to target neutrophil activation and migration.” (8) I am not advocating relegating dapsone to the dustbin in favor of propranolol — yet. Should further studies prove its efficacy (we are already familiar with its tolerable adverse reactions), I would be delighted to add it to my therapeutic palate for NDs.

Point to Remember: The uses of propranolol (and other nonselective β-blockers) continues to expand in dermatology, perhaps even having a therapeutic potential for neutrophil-mediated disorders.

Our expert’s viewpoint

David A. Wetter, MD, FAAD

Professor of Dermatology

Mayo Clinic

Rochester, Minnesota

As it becomes increasingly time-intensive to obtain approval for treatments of complex medical dermatologic diseases (9), it is heartening to see a potential “new” use of an “old” medication (propranolol) for epidermolysis bullosa acquisita (EBA) and other neutrophil-mediated skin diseases (7,8). Given that the overarching treatment goal for many complex medical dermatologic conditions is to control and suppress the disease (rather than cure it), it remains paramount that we have a variety of safe and effective corticosteroid-sparing systemic agents at our disposal when treating severe diseases requiring prolonged courses of therapy over many years. During the COVID-19 pandemic, this is of particular clinical relevance, as dermatologists seek to safely utilize immunosuppressive medications for their patients while minimizing the concomitant risk of serious complications from infection with SARS-CoV-2 (10).

Earlier this week one of my colleagues discussed a patient with me whose bullous pemphigoid was not responding to prednisone and doxycycline. Given the patient’s medical comorbidities, conventional immunosuppressive medications such as mycophenolate mofetil and methotrexate were not feasible. My colleague was considering utilizing rituximab for his patient, but expressed concern that it could blunt the patient’s ability to mount a protective immune response to the upcoming COVID-19 vaccine (10). Analogous to the novel use of propranolol for EBA, my colleague cited recent literature demonstrating the promise of off-label use of dupilumab for bullous pemphigoid (11), and elected to pursue (pending insurance approval) dupilumab therapy for his patient. This vignette highlights another example of the dermatological community finding a new and effective use for a well-described non-immunosuppressive systemic medication in patients with chronic and severe skin disease.

While perusing the study of Stüssel et al (7), I was interested to learn that one of the ways that propranolol can exert anti-inflammatory effects is through the “modulation of tumor necrosis factor (TNF)” and that this “observation could also have implications for the treatment of other (partially) neutrophil-dependent diseases like allergic skin inflammation, psoriasis, Sweet disease, and anaphylactoid purpura (IgA vasculitis).” The “yin and yang” of TNF-alpha inhibition (12) — how a medication used to treat a given condition can sometimes paradoxically induce or worsen that very same condition — has fascinated me since the end of my dermatology residency, and spurred me to investigate our Mayo Clinic experience regarding several TNF-alpha inhibitor-induced diseases (lupus, psoriasis, and vasculitis) (13-15). It is therefore worthwhile to speculate whether propranolol (in select instances) could paradoxically worsen some of the neutrophil-dependent diseases (such as psoriasis and cutaneous small-vessel vasculitis) that Stüssel et al (7) postulate it could treat, especially given that beta-blockers are a well-known cause of drug-induced psoriasis. Nonetheless, the expanding role of propranolol through its immunomodulatory effects on neutrophils is an exciting development for medical dermatologists, given the need for safe and effective long-term treatments of the varied neutrophil-mediated diseases that we routinely encounter in clinical practice.

Oberlin KE. Expanding uses of propranolol in dermatology. Cutis. 2017 Apr;99(4):E17-E19.

Horst C, Kapur N. Propranolol: a novel treatment for angiolymphoid hyperplasia with eosinophilia. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2014 Oct;39(7):810-2.

Choeyprasert W, Natesirinilkul R, Charoenkwan P. Successful treatment of mild pediatric kasabach-merritt phenomenon with propranolol monotherapy. Case Rep Hematol. 2014;2014:364693.

Logger JGM, Olydam JI, Driessen RJB. Use of beta-blockers for rosacea-associated facial erythema and flushing: A systematic review and update on proposed mode of action. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2020 Oct;83(4):1088-1097

Frolov VA, Moiseeva EG, Pasechnik AV. Pathophysiological aspects of functional modulation of human peripheral blood neutrophils with propranolol. Bull Exp Biol Med. 2006 Jun;141(6):675-7. English, Russian.

Marzano AV, Ortega-Loayza AG, Heath M, Morse D, Genovese G, Cugno M. Mechanisms of Inflammation in Neutrophil-Mediated Skin Diseases. Front Immunol. 2019 May 8;10:1059.

Stüssel P, Schulze Dieckhoff K, Künzel S, Hartmann V, Gupta Y, Kaiser G, Veldkamp W, Vidarsson G, Visser R, Ghorbanalipoor S, Matsumoto K, Krause M, Petersen F, Kalies K, Ludwig RJ, Bieber K. Propranolol Is an Effective Topical and Systemic Treatment Option for Experimental Epidermolysis Bullosa Acquisita. J Invest Dermatol. 2020 Dec;140(12):2408-2420.

Maglie R, Solimani F, Quintarelli L, Hertl M. Propranolol Off-Target: A New Therapeutic Option in Neutrophil-Dependent Dermatoses? J Invest Dermatol. 2020 Dec;140(12):2326-2329. doi: 10.1016/j.jid.2020.06.002. PMID: 33222759.

Jew OS, Okawa J, Barbieri JS et al. Evaluating the effect of prior authorizations in patients with complex dermatologic conditions. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2020;83:1674-80.

Zahedi Niaki O, Anadkat MJ, Chen ST et al. Navigating immunosuppression in a pandemic: A guide for the dermatologist from the COVID Task Force of the Medical Dermatology Society and Society of Dermatology Hospitalists. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2020;83:1150-9.

Abdat R, Waldman RA, de Bedout V et al. Dupilumab as a novel therapy for bullous pemphigoid: A multicenter case series. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2020;83:46-52.

Fiorentino DF. The yin and yang of TNF-α inhibition. Arch Dermatol. 2007;143:233-6.

Wetter DA, Davis MDP. Lupus-like syndrome attributable to anti-tumor necrosis factor α therapy in 14 patients during an 8-year period at Mayo Clinic. Mayo Clin Proc. 2009;84:979-84.

Shmidt E, Wetter DA, Ferguson SB, Pittelkow MR. Psoriasis and palmoplantar pustulosis associated with tumor necrosis factor-α inhibitors: The Mayo Clinic experience, 1998-2010. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2012;67:e179-85.

Sokumbi O, Wetter DA, Makol A, Warrington KJ. Vasculitis associated with tumor necrosis factor-α inhibitors. Mayo Clin Proc. 2012;87:739-45.

All content found on Dermatology World Insights and Inquiries, including: text, images, video, audio, or other formats, were created for informational purposes only. The content represents the opinions of the authors and should not be interpreted as the official AAD position on any topic addressed. It is not intended to be a substitute for professional medical advice, diagnosis, or treatment.

DW Insights and Inquiries archive

Explore hundreds of Dermatology World Insights and Inquiries articles by clinical area, specific condition, or medical journal source.

All content solely developed by the American Academy of Dermatology

The American Academy of Dermatology gratefully acknowledges the support from Incyte Dermatology.

Make it easy for patients to find you.

Make it easy for patients to find you.

Meet the new AAD

Meet the new AAD

2022 AAD VMX

2022 AAD VMX

AAD Learning Center

AAD Learning Center

Need coding help?

Need coding help?

Reduce burdens

Reduce burdens

Clinical guidelines

Clinical guidelines

Why use AAD measures?

Why use AAD measures?

Latest news

Latest news

New insights

New insights

Combat burnout

Combat burnout

Joining or selling a practice?

Joining or selling a practice?

Advocacy priorities

Advocacy priorities

Promote the specialty

Promote the specialty