Targeted anti-complement therapy may prove to be a complementary treatment for bullous pemphigoid

By Warren R. Heymann, MD

Oct. 7, 2020

Vol. 2, No. 40

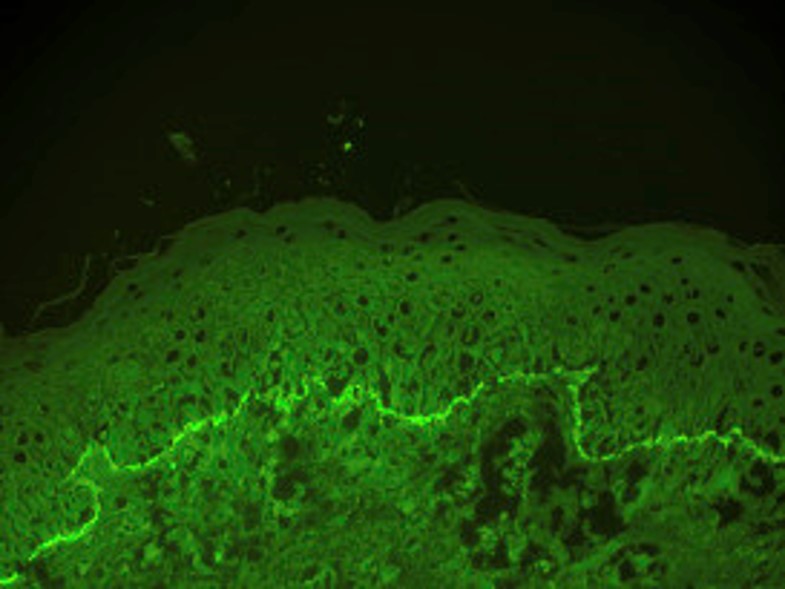

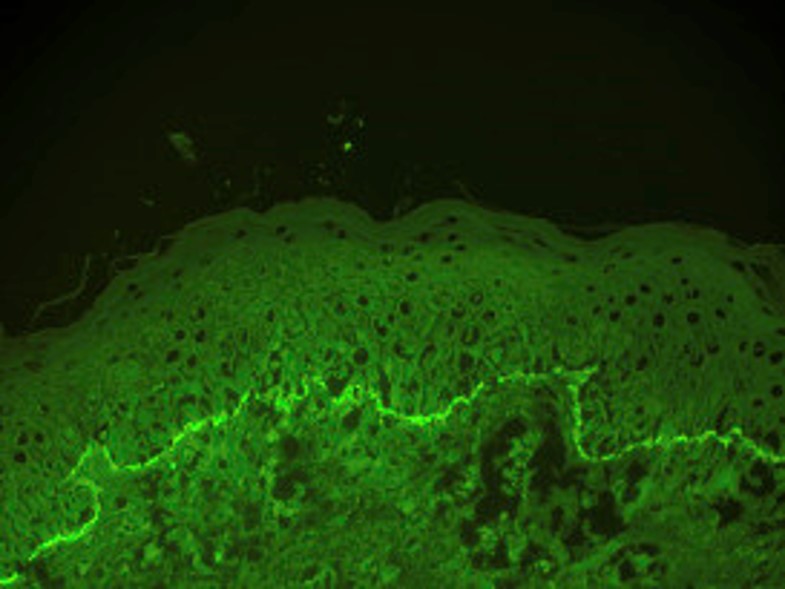

Diagnosing BP is based on demonstrating eosinophilic spongiosis or a subepidermal detachment with eosinophils on routine histology; the detection of IgG and/or C3 deposition at the basement membrane zone using direct or indirect immunofluorescence assays; and quantification of circulating autoantibodies against BP180 and/or BP230 using ELISA. The pathogenesis of BP is based on a dysregulated T cell immune response and synthesis of IgG and IgE autoantibodies against hemidesmosomal proteins (BP180 and BP230) resulting in neutrophil chemotaxis and degradation of the basement membrane zone. (1)

According to Genovese et al, “The pathogenic mechanisms cooperating in the blister formation secondary to BP autoantibody binding to their targets are complex and may be subdivided into complement-dependent and complement-independent ones. Indeed, IgG1 has been demonstrated to start the inflammatory complement cascade leading to the recruitment of neutrophils and eosinophils in BP, and, consequently, the release of proteolytic enzymes in an experimental mouse model of BP.” Additionally, there is increasing evidence that complement-independent pathways play a fundamental role in BP pathogenesis. It has been postulated that there may be a direct influence of autoantibodies in adhesion functions of autoantigens. (3)

Bartko et al asserted that targeting complement factor C1s by the humanized monoclonal antibody sutimlimab provides highly selective inhibition of the classical complement pathway. “Sutimlimab is a humanized monoclonal IgG4 antibody directed against human complement factor C1s, a serine protease responsible for the enzymatic propagation of the classical complement pathway (CP). C1s is part of the C1 complex, a multimeric protein assembly containing the pattern recognition receptor C1q and the C1s‐activating serine protease, C1r. By binding C1s, sutimlimab specifically inhibits the classical pathway, preventing the enzymatic action of the C1 complex on its substrates (C4 and C2), thereby blocking formation of the pivotal enzyme, C3‐convertase. Importantly, sutimlimab preserves the function of both the alternative and lectin complement pathways to mediate humoral surveillance of pathogens. Sutimlimab also leaves the opsonic function of C1q (i.e., phagocytic clearance of apoptotic cellular debris) intact.” In their phase I, first-in-human, double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled, dose-escalation trial of sutimlimab or placebo conducted in 64 volunteers, infusions of sutimlimab were well tolerated without any safety concerns. The authors concluded that their study established the foundation for using sutimlimab as a highly selective inhibitor of the classical complement pathway in different diseases. (4) Indeed, sutimlimab has shown favorable activity in cold agglutinin disease. (5)

Freire et al evaluated the safety and activity of sutimlimab in 10 subjects with active or past bullous pemphigoid. Four weekly 60 mg/kg infusions of sutimlimab proved sufficient for inhibition of the classical complement pathway in all patients, as measured by CH50. C3c deposition along the dermal-epidermal junction was partially or completely abrogated in 4 of 5 patients, where it was present at baseline. Sutimlimab probably did not affect the natural decay of previously deposited complement, but rather prevented new complement deposition. Strikingly, in parallel with C3c, IgG deposition was completely or partially abolished in 4 out of 6 treated patients, despite serum titers not being affected. The mechanism behind this phenomenon is not understood, warranting further scrutiny. Sutimlimab was found to be safe and tolerable in this study, with only mild to moderate adverse events reported (e.g., headache, fatigue). One serious adverse event (fatal cardiac decompensation) occurred at the end of the post-treatment observation period in an 84-year-old patient with a history of diabetes and heart failure but was considered unlikely to be drug-related. The authors concluded that their findings support further studies for sutimlimab’s efficacy and safety in BP patients. (6)

I must compliment this novel approach exploring targeted anti-complement therapy for BP patients. Complementary studies are certainly warranted to determine its precise role in managing BP.

Point to Remember: Novel targeted therapy with the monoclonal antibody sutimlimab, directed against complement factor C1s, may prove efficacious in patients with bullous pemphigoid and other complement-mediated disorders.

Our Experts’ Viewpoints

Nicole Fett, MD, MSCE

Dermatology Residency Program Director

Associate Professor of Dermatology

Oregon Health and Science University

Despite the large armamentarium available to treat bullous pemphigoid, there remain patients who are refractory to therapy or who are not candidates for therapies based on their comorbidities. I have recently just lost such a patient — a delightful woman in her 80s whose bullous pemphigoid was refractory to tetracyclines with niacinamide, dapsone, and IVIG, who developed anemia and recurrent sepsis with low dose methotrexate and therefore was reluctant to trial additional immunosuppressive steroid sparing disease modifying agents. The heartbreak of these patients always drives us to be more creative and innovative with our therapies. A new steroid sparing therapy without immunosuppressive complications would be a welcome addition in the treatment of bullous pemphigoid. As Ricklin et al have recently declared, we are in a renaissance of complement therapeutics. (7) Complement inhibitors are being investigated in the treatment of cold agglutinin disease, thrombotic microangiopathies, hemolytic uremic syndrome, kidney transplantation, transplant rejection, periodontitis, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, paroxysmal nocturnal hemoglobinuria, age-related macular degeneration, anti-neutrophilic cytoplasmic-antibody-associated vasculitis, antiphospholipid syndrome, graft versus host disease, lupus nephritis, hidradenitis suppurativa, Alzheimer disease, Huntington disease, ALS, multiple sclerosis, transplant-associated microangiopathy, uveitis, and sepsis to name a few. Complement inhibition was, until Friere’s study, an unstudied pathogenic target of bullous pemphigoid. The study is a phase 1 study (focused on safety and therefore no conclusions can be drawn about efficacy) of sutimlimab, a humanized monoclonal IgG4 antibody against C1s, in patients with bullous pemphigoid. Ninety percent of the enrolled subjects had an adverse event. There was no age and comorbidity matched placebo group from which to draw comparison. The authors report that all 10 enrolled subjects had minimal to no bullous pemphigoid disease activity at the time of enrollment. Despite lack of disease activity, 5/8 subjects had C3c deposition and 6/8 had IgG deposition along the basement membrane zone on their baseline DIFs. 3/5 of these patients had decrease in C3c deposition on DIF during sutimlimab therapy. Given the very small sample size (10 subjects), the 90% adverse event rate, one death (likely unrelated to therapy), and the lack of efficacy data, we are far away from using sutimlimab in the therapy of bullous pemphigoid. However, given complement inhibition’s success in other antibody mediated diseases, I remain hopeful that sutimlimab may prove to be efficacious after additional investigation and will provide us with an additional option in the treatment of refractory bullous pemphigoid. If this is the case, it is important to remember that the complement system plays a pivotal role in the control of encapsulated bacterial pathogens (Neisseria meningitides, Haemophilus influenza, and Steptococcus penumoniae) and therefore patients should already be vaccinated, or receive vaccination against these organisms at least 14 days prior to receiving sutimlimab.

Dr. Fett had disclosed financial relationships with the following to the AAD at the time of publication: LaRoche Posay, Pfizer. Full disclosure information is available at coi.aad.org.

Miyamoto D, Santi CG, Aoki V, Maruta CW. Bullous pemphigoid. An Bras Dermatol 2019; 94: 133-146.

Kaye A, Gordon SC, Deverapalli SC, Her MJ, Rosmarin D. Dupilumab for the treatment of recalcitrant bullous pemphigoid. JAMA Dermatol 2018; 154: 1225-1226.

Genovese G, Di Zenso G, Cozzani E, Berti E, et al. New insights into the pathogenesis of bullous pemphigoid: 2019 update. Front Immunol 2019; 10: 1506.

Bartko J, Schoergenhofer C, Schwameis M, Firbas C, et al. A randomized, first-in-human healthy volunteer trial of sutimlimab, a humanized antibody for the specific inhibition of the classical complement pathway. Clin Pharmacol Ther 2018; 104: 655-663.

Berensten S, Hill A, Hill QA, Tvedt THA, Michel M. Novel insights into the treatment of complement-mediated hemolytic anemias. Ther Adv Hematol 2019; 10:2040620719873321.

Freire PC Muñoz CH, Derhaschnig U, Schoergenhofer C, et al. Specific inhibition of classical complement pathway prevents C3 deposition along the dermal-epidermal junction in bullous pemphigoid. J Invest Dermatol 2019; 139: 2417-2424.

Ricklin D, Mastellos DC, Reis ES, and JD Lambris. The renaissance of complement therapeutics. Nature Reviews Nephrology. 2018. 14:26-47.

All content found on Dermatology World Insights and Inquiries, including: text, images, video, audio, or other formats, were created for informational purposes only. The content represents the opinions of the authors and should not be interpreted as the official AAD position on any topic addressed. It is not intended to be a substitute for professional medical advice, diagnosis, or treatment.

DW Insights and Inquiries archive

Explore hundreds of Dermatology World Insights and Inquiries articles by clinical area, specific condition, or medical journal source.

All content solely developed by the American Academy of Dermatology

The American Academy of Dermatology gratefully acknowledges the support from Incyte Dermatology.

Make it easy for patients to find you.

Make it easy for patients to find you.

Meet the new AAD

Meet the new AAD

2022 AAD VMX

2022 AAD VMX

AAD Learning Center

AAD Learning Center

Need coding help?

Need coding help?

Reduce burdens

Reduce burdens

Clinical guidelines

Clinical guidelines

Why use AAD measures?

Why use AAD measures?

Latest news

Latest news

New insights

New insights

Combat burnout

Combat burnout

Joining or selling a practice?

Joining or selling a practice?

Advocacy priorities

Advocacy priorities

Promote the specialty

Promote the specialty