Eruptive pseudoangiomatosis is real

By Warren R. Heymann, MD, FAAD

May 4, 2022

Vol. 4, No. 18

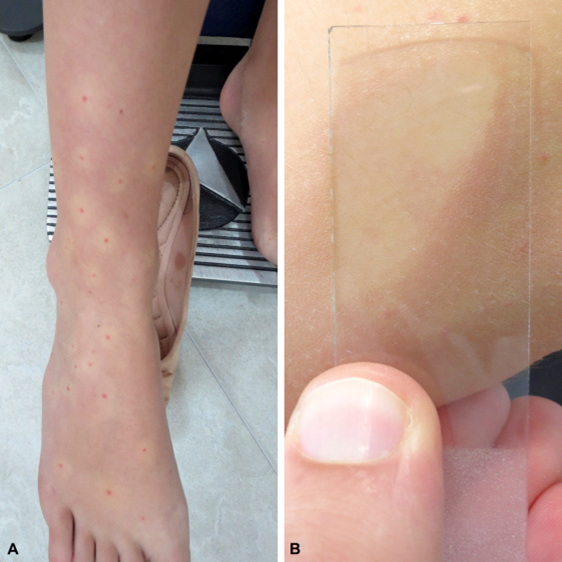

In 1969, Cherry et al described “acute hemangioma-like lesions” in 4 children aged 8 to 11 months; ECHO 25 virus was isolated in 2 patients and ECHO 32 was recovered from the other 2. “The hemangioma-like lesions in all four children were similar in appearance and in their sparseness of distribution. The basic lesion was a small erythematous papule with a central pinpoint vascular supply. Pressure on this central vessel caused blanching of the whole papule. Surrounding the papule was a halo which was relatively avascular when compared with the uninvolved skin.” The authors hypothesized that these lesions could be due to a direct viral effect or “they could be a secondary occurrence following an antigen union at the vascular site.” (3)

Prose et al coined the term EP after describing 3 patients aged 6 months to 6 years with presumed viral illnesses, with similar lesions as described by Cherry et al, that resolved within days. A biopsy from the 6-year-old boy revealed several dilated capillaries in the papillary and upper reticular dermis, lined by endothelial cells with a “hobnail” appearance, with an attendant sparse lymphohistiocytic infiltrate. The number of blood vessels was not increased. Electron microscopy failed to reveal viral particles. The authors noted that EP can be distinguished from bacillary angiomatosis and pyogenic granulomas clinically and histologically. They surmised that EP is a viral exanthem, although it could be “an unusual reaction pattern to several different organisms.” (4) Subsequent authors consider EP to be a “paraviral” eruption, in the same genre as Gianotti-Crosti syndrome or asymmetric periflexural exanthem of childhood. (5)

Prose et al were prescient in predicting that EP would be reported with other viruses; indeed, Epstein-Barr virus, cytomegalovirus, adenovirus infections, Parvovirus B19, HIV, SARS-CoV-2 (COVID-19), and vaccinations have all been implicated as pathogenic. (5,6,7,8) Mohta et al reported 5 patients with EP after receiving the adenovirus coronavirus vaccine Covishield. The mean duration between vaccination and development of eruptions was 5.2 days, with complete resolution within 10 days. (6) In a subsequent series, Mohta et al reported 51 cases of EP in adults following administration of Covishield. This was observed following the second dose in 47 patients (88.7%). (9) A case of EP was reported in a 51-year-old woman 10 days following administration of the Moderna mRNA COVID-19 vaccine. These lesions coalesced on the vaccination arm, reminiscent of “COVID-arm,” but were also generalized with predominantly acral lesions. The EP cleared within a week. (10) Zengarini et al reported “eruptive cherry angiomatosis” in a 64-year-old woman, 5 days after receiving the second dose of her Pfizer mRNA vaccine. She developed “32 bleachable reddish papules of 2–3 mm of diameter during physical examination, surrounded by a pale perilesional halo, on the trunk, limbs and back… biopsy of the most representative lesion showed dilated interconnecting capillaries rich in erythrocytes with no cytological atypia.” (11) Aside from the fact that these lesions were still present a month later, I suspect that these fall under the umbrella of EP rather than cherry angiomas.

While most common in children, EP may be observed in adults. Triggers other than viruses have included insect bites (which may represent the same condition as erythema punctatum Higuchi), acute lymphoblastic leukemia, Hodgkin lymphoma, non-Hodgkin lymphoma, and chemotherapy. (7,12, 13)

Dermoscopy demonstrates consistent findings in EP, manifested by dotted vessels over an enlarged vascular network, surrounded by a diminished vascular network or structureless areas. (14, 15).

As lesions of EP are self-limited, there is no need to treat them. EP may be pruritic (6,7), so the use of topical steroids may be considered.

EP are fascinating, enigmatic lesions. I sense that the key to their mystery lies not in the vessels themselves, but rather the cytokine milieu from the perivascular infiltrate. Further studies should help determine what cytokine cocktail promotes these lesions.

Point to Remember: Although eruptive pseudoangiomatosis is usually encountered in children with viral syndrome, there are increasing reports in adults, including those with COVID-19, vaccination against SARS-CoV-19, and other conditions.

Our expert’s viewpoint

Alpana Mohta, MBBS, MD, DNB

Imrich Sarkany Non-European Memorial Scholar

Senior Resident

Sardar Patel Medical College, Bikaner

Rajasthan, India

In late 2019 the world was abruptly hit by the deadly novel Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) and the entire human race has been trying to recover from its rampant rage ever since. Fortunately, within less than a year, competent researchers from across the globe serving humanity came up with effective vaccination strategies for the heinous virus. There have been numerous reports of mucocutaneous manifestations following vaccination and infection with COVID-19. (16)

These lesions were first described by Cherry et al who described their presence in 4 pediatric patients infected with echovirus. (3) The first adult case was reported in 2000 by Navarro et al. (17) The disease is believed to be of a paraviral origin. It is an underdiagnosed entity characterized by the development of sudden asymptomatic angiomatous lesions with a blanched perilesional halo. While pediatric patients may experience prodromal symptoms, adult cases are invariably asymptomatic.

Cases of EP following COVID-19 infection and vaccination are being increasingly reported. Alonzo Caldarelli A et al published one of the first reports of post-vaccine EP. (8) Vaccine-induced EP is thought to result from an upregulation of cellular and humoral immunity towards the spike protein present in the viral vaccine, creating a paraviral response. According to our experience, the incidence of post-COVID-19 vaccine-related EP is around 0.03%. (9)

As vaccination coverage increases across the globe, we will begin to peel back the layers of the onion. In order to combat vaccine hesitancy, it is important to distinguish vaccine adverse events which can be managed with symptomatic treatment (the majority of patients) from the rare ones. It is imperative to clearly explain to patients and providers alike that EP is a benign and self-resolving dermatosis, and not a contraindication for subsequent doses of the vaccine.

Kudur MH, Hulmani M. "Pseudo" conditions in dermatology: need to know both real and unreal. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2012 Nov-Dec;78(6):763-73. doi: 10.4103/0378-6323.102387. PMID: 23075655.

Ghosh S, Jain VK. "Pseudo" Nomenclature in Dermatology: What's in a Name? Indian J Dermatol. 2013 Sep;58(5):369-76. doi: 10.4103/0019-5154.117305. PMID: 24082182; PMCID: PMC3778777.

Cherry JD, Bobinski JE, Horvath FL, Comerci GD. Acute hemangioma-like lesions associated with ECHO viral infections. Pediatrics. 1969 Oct;44(4):498-502. PMID: 5346628.

Prose NS, Tope W, Miller SE, Kamino H. Eruptive pseudoangiomatosis: a unique childhood exanthem? J Am Acad Dermatol. 1993 Nov;29(5 Pt 2):857-9. doi: 10.1016/0190-9622(93)70255-r. PMID: 7980731.

Maqsood F, Vassallo C, Derlino F, Croci GA, Ciolfi C, Brazzelli V. Eruptive Pseudoangiomatosis: Clinicopathological Report of 20 Adult Cases and a Possible Novel Association with Parvovirus B19. Acta Derm Venereol. 2021 Feb 16;101(2):adv00398. doi: 10.2340/00015555-3761. PMID: 33554264.

Mohta A, Jain SK, Mehta RD, Arora A. Development of eruptive pseudoangiomatosis following COVID-19 immunization - Apropos of 5 cases. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2021 Nov;35(11):e722-e725. doi: 10.1111/jdv.17499. Epub 2021 Jul 24. PMID: 34236736; PMCID: PMC8447312

González Saldaña S, Mendez Flores RG, López Gutiérrez AF, Salas Núñez LN, Hermosillo Loya AK, Ramírez Padilla M, Hernández Torres M. Eruptive pseudoangiomatosis in adults with immune system disorders: A report of two cases. Dermatol Reports. 2020 Dec 22;12(3):8836. doi: 10.4081/dr.2020.8836. PMID: 33408842; PMCID: PMC7772766.

Alonzo Caldarelli A, Barba P, Hurtado M. Eruptive pseudoangiomatosis and SARS-CoV-2 (COVID-19) infection. Int J Dermatol. 2021 Aug;60(8):1028-1029. doi: 10.1111/ijd.15598. Epub 2021 Apr 13. PMID: 33846968; PMCID: PMC8251449.

Mohta A, Sharma MK, Ghiya BC, Mehta RD. Clinical, histopathological, and dermatoscopic characterization of eruptive pseudoangioma developing after COVID-19 vaccination-A case-series. J Cosmet Dermatol. 2022 Feb 20. doi: 10.1111/jocd.14870. Epub ahead of print. PMID: 35184375.

Moya-Martinez C, Berná-Rico ED, Melian-Olivera A, Moreno-Garcia Del Real C, Fernández-Nieto D. Comment on 'Development of eruptive pseudoangiomatosis following COVID-19 inmunization-apropos of 5 cases': could eruptive pseudoangiomatosis represent a paraviral eruption associated with SARS-CoV-2? J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2022 Feb;36(2):e95-e97. doi: 10.1111/jdv.17750. Epub 2021 Oct 29. PMID: 34657329.

Zengarini C, Misciali C, Lazzarotto T, Dika E. Eruptive angiomatosis after SARS-CoV-2 vaccine (Comirnaty, Pfizer). J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2022 Feb;36(2):e90-e91. doi: 10.1111/jdv.17723. Epub 2021 Oct 29. PMID: 34606666.

Mori A, Kaku Y, Dainichi T. Erythema punctatum Higuchi: reconsidering its relationship with adrenergic urticaria and eruptive pseudoangiomatosis. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2021 Nov;35(11):e792-e793. doi: 10.1111/jdv.17474. Epub 2021 Jul 13. PMID: 34171183.

Rivas-Calderón MK, Morán-Villaseñor E, Maza-Ramos G, Orozco-Covarrubias L, Corcuera-Delgado CT, Sáez-de-Ocariz M. Eruptive pseudoangiomatosis in two children with acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Int J Dermatol. 2018 Jul;57(7):e38-e40. doi: 10.1111/ijd.14030. Epub 2018 May 8. PMID: 29740813.

Wambier CG, Cappel MA, Danilau Ostroski TK, Montemor Netto MR, de Farias Wambier SP, Santos de Jesus BL, Arruda E. Familial outbreak of eruptive pseudoangiomatosis with dermoscopic and histopathologic correlation. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2017 Feb;76(2S1):S12-S15. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2016.03.049. PMID: 28087016.

Kushwaha RK, Mohta A, Jain SK. A Case of Eruptive Pseudoangiomatosis: Clinical, Histopathological, and Dermoscopic Findings. Indian Dermatol Online J. 2020 Jan 24;11(4):672-673. doi: 10.4103/idoj.IDOJ_407_19. PMID: 32832476; PMCID: PMC7413426.

Burlando M, Herzum A, Micalizzi C, Cozzani E, Parodi A. Cutaneous reactions to COVID-19 vaccine at the dermatology primary care. Immun Inflamm Dis. 2022;10(2):265-271.

Navarro V, Molina I, Montesinos E, Calduch L, Jordá E. Eruptive pseudoangiomatosis in an adult. Int J Dermatol 2000;39:237-8.

All content found on Dermatology World Insights and Inquiries, including: text, images, video, audio, or other formats, were created for informational purposes only. The content represents the opinions of the authors and should not be interpreted as the official AAD position on any topic addressed. It is not intended to be a substitute for professional medical advice, diagnosis, or treatment.

DW Insights and Inquiries archive

Explore hundreds of Dermatology World Insights and Inquiries articles by clinical area, specific condition, or medical journal source.

All content solely developed by the American Academy of Dermatology

The American Academy of Dermatology gratefully acknowledges the support from Incyte Dermatology.

Make it easy for patients to find you.

Make it easy for patients to find you.

Meet the new AAD

Meet the new AAD

2022 AAD VMX

2022 AAD VMX

AAD Learning Center

AAD Learning Center

Need coding help?

Need coding help?

Reduce burdens

Reduce burdens

Clinical guidelines

Clinical guidelines

Why use AAD measures?

Why use AAD measures?

Latest news

Latest news

New insights

New insights

Combat burnout

Combat burnout

Joining or selling a practice?

Joining or selling a practice?

Advocacy priorities

Advocacy priorities

Promote the specialty

Promote the specialty